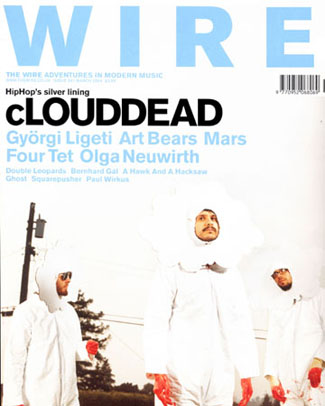

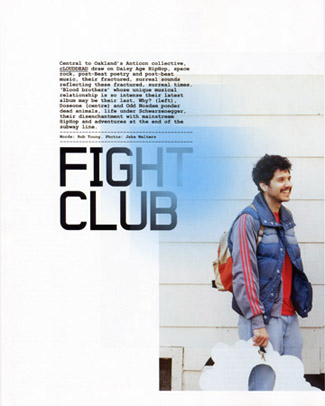

FIGHT CLUB

Central to Oakland's Anticon collective, cLOUDDEAD draw on Daisy Age HipHop, space rock, post-Beat poetry and post-beat music, their fractured, surreal sounds reflecting these fractured, surreal times. 'Blood brothers' whose unique musical relationship is so intense their latest album may be their last, why? (left), Doseone (centre) and odd nosdam ponder dead animals, life under Schwarzenegger, their disenchantment with mainstream HipHop and adventures at the end of the subway line.

Knock knock. Who's there? Cloud. Cloud who?

Clouded

So Adam was talking to his four year old sister and she told him a knock-knock joke. And Adam, who was in Greenthink at the time, was on the phone to his bandmate Yoni, and he was like, "I got a name for us, man," Yoni was in Spain, and he couldn't see it at first, but then he started thinking about it and he was like, "Yeah, cLOUDDEAD, that's what we should use."

Adam Drucker is better known as Doseone; Yoni is the handle of one Jonathan Wolf, who trades under a question mark: why?. Yoni had a buddy, Dave Madson, also known as odd nosdam. Once they all lived in Cincinnati, Ohio. As G Dubya hacked out a swathe of three million lost jobs across the US, Ohio became the fastest industrial declining state. Maybe they were feeling the entropy around 2000, because it was then they felt something small and insectoid was calling them away, away from Ohio and over to California. And they went up there, to a land of opportunity, and met up with a whole bunch of folks who walked and talked exactly like them.

COALITION OF THE UNWILLING

In Chuck Palahniuk's 'Fight Club', the novel immortalized by David Fincher's 1999 film, a cult of disaffected American males coalesces around two charismatic leaders (one turning out to be a paranoid delusion of the other). They live on the edge of the city, battle themselves and strangers, and develop strategies to inject society with increasingly anarchistic acts, all enacted, at bottom, to rescue a declining sense of control over their destiny. Talking to the various "moody folks" associated with Oakland's Anticon collective, of which cLOUDDEAD is one of the central clots, you detect a similar kind of cultish collectivization, built on a shared mistrust of what and who the world wants you to be (even though, despite their frequent arguments, you can't picture them breaking each others' faces on a regular basis).

"There's something very real and rich about cLOUDDEAD," says odd nosdam. "There's something really unique about it that I can't put my finger on, that seems to happen when we work together."

"It really is a blood brother situation," agrees Doseone, his unmistakable voice ringing clear over a remarkably good phone link considering he's half a world away. "And sometimes it's harder to be there just beside them when you know you've taken an oath that you'll never leave them." But living all over each other, as they have done, comes with it's own complications. "It's really hard," emphasizes Doseone, "to believe in your friend as this incredible artist that you share all this incredible stuff with, and then you're cleaning his dishes." This intensity is part of the reason why 'Ten', released this month on Ninja Tune sister label Big Dada (in Europe) and Mush (in the US), is the second and by their own admission, probably the final cLOUDDEAD record.

The full story of the Anticon members' peregrinations was told by Peter Shapiro in The Wire 225, but to focus on cLOUDDEAD (the Ohio chapter), the trio's roots stem from the late 90's, when Doseone escaped from a looming career in marketing by transforming himself into a full throttle rap MC in Cincinnati. While still at university, he met Jonathan 'Yoni' Wolf, aka why?, and formed a group called Apogee with tricksy turntablist Mr Dibbs and his brother Josiah. While working with Doseone on a second project, Greenthink, Yoni brought his school friend Dave Madson (odd nosdam), a devotee of 90s space rock, into play.

Anticon's soldiers began to muster between 1998-2000 in Oakland, California, from various points east throughout the US. They all lived together for a while in a shared house, on call to make music 24 hours a day. Out of his honeycomb has come as incredible amount of music projects yet to be assimilated, but with a growing core following: the individual musics of Sole, Doseone, Alias, odd nosdam, why?, The Pedestrian, Slug; the groups Deep Puddle Dynamics, Greenthink, Reaching Quiet, Themselves, Subtle and cLOUDDEAD; the spin-offs and side projects with Boom Bip, Hymie's Basement, satellite likeminds Buck 65 and Sage Francis, productive links forged with post-rock groups such as England's Hood and Germany's Notwist. Their music is as related to HipHop as, say, Nirvana were to the blues: the last remaining bridge to origins burnt long ago. Over the past six years of Anticon's existence, all their musics have imploded under the pressure of their urgently communicating voices.

"None of us feel at home," whines Doseone. "We're all very angsty, moody folks. That is definitely our nature. It's because of the gaps in relation that we all had through our childhood and teen years, twenties, became exactly why we could relate to each other. Anyone that's really close to you - you don't have to explain the things that intrigue you with people that you surround yourself with."

For Doseone, the angst kicked in early, at "11-ish, the beginning of double digits, and it just grew. When I moved a lot, whatever got me punched in the face at one school, I could never do again. I moved every two years and I was always in the shitty inner city schools. Social survival took precedence over everything. It took me to where I needed to be, though: to the edge of the rap battle maniac thing that I was doing, and that was somehow a good place to start all over again, with open mind. I never felt like I fitted in until I met the oddballs. This is weird - it's not so much about us fitting in; we just don't fit into the general world picture, the picture of the world in our heads never seemed to fit us."

HipHop, not before time, has become an internationally recognized fraternity around which society's discontents can shore up their sense of identity. "You can be a superhero, totally!" he agrees. "Yeah, you can do whatever you want. HipHop at its most frivolous and creative era was full of ridiculous offshoots of personality. There was Snaggapuss, he was down with Brand Nubian and he rapped like Snagglepuss, the fuckin' Hanna Barbera character.

There's something about rap that lends itself to having theme songs. Whereas with a rock band you end up doing love songs, rap seems to be the theme-song generator. You score your life in a sense and that got very perverted with us. We lived in a house with our recording devices, our style came completely out of that creating a total escape.

"We didn't have a peer group around us when we were shedding skin and recording a lot, so we got into creating that escape and then not keeping any rules once you got there."

All three seem uncomfortable with the process of taking their music to the people via performance - a necessary evil that nevertheless forces them to drag out the devils within them. Doseone especially can summon a form of address that can be shocking and scary in its intensity, whether on a previous cLOUDDEAD tour or in his appearances with Themselves and Subtle. Having seen him cussing out the Devil, confessing suicidal urges through a vocoder, oscillating wildly and adlibbing wittily during various Themselves gigs over the past couple of years, I was convinced he must have a background at drama school, but he assures me that's not the case. Instead, it comes from somewhere inside. "Me being a maniac on stage for four or five months out of the year completely balances my drinking diet soda and smoking pot in front of a computer working on music and writing poems, you know? I reserve the right to be childish and put my obsessions everywhere."

The twin vocal attack of Doseone and why? spearheads cLOUDDEAD's front line. "There's something about overload that I really like," says Doseone when I quiz him on his mach speed vocal delivery. "The fast rap overload of well written lines is what I really fetishised as a kid. My best poems, I wanna do them at 100 miles an hour and see how that feels." Doseone's voice has been immortally and definitively nailed (by Peter Shapiro again) as "a wisecracking Jewish duck reincarnated as Percy Bysshe Shelley, or a Beatnik Marge Simpson after assertiveness training", a description impossible to refute. It's not for everyone. HipHop has been around so long now, that a voice that isn't ranting, heckling, bigging up self or acquaintances, props-spraying and generally hating, is vox non grata. Like the breakbeat brats a few years ago (Squarepusher, u-Zig, Autechre et al), the laughing stock of 'true' Junglists, it takes mavericks and those from outside the tradition to point up how hidebound the tradition really is: to hold the distorting mirror up to its claims to freedom and openness.

They may spit 100 words a minute into the mix, but this is far from braggart self-promotion. What sets cLOUDDEAD apart is the unusual nature of the lyrics - dense, allusive linguistic nets, rich with observational intricacy, with a fresh, wondering gaze. The veil of 'home sweet home' is lifted to reveal a macabre hornet's nest - the Alice in Wonderland trick. I'm also put in mind of late 60s American pop uncanny: Pearls Before Swine's folk-melancholic 'Balaklava, and Love's 'Forever Changes', both in their different ways laments and confused trips inspired by the Vietnam debacle (only substitute 'Nam for the Gulf). Boards of Canada provided a pop-psych remix of the new cLOUDDEAD single "Dead Dogs Two", which underlines the San Franciscans' kinship with the candy-twisted, ice-sculpted Songshapes newly minted from the electronica leftfield that gives you Tujiko Noriko, So, Fog, and so on. The explosion of new American fiction is also relevant here: the prose of David Foster Wallace (who contributed to the 1990 book 'Signifying Rappers'), Dave Eggers and his experimental literary journal McSweeney's, Chuck Palahnuik, Jonathan Safran Foer and Jeffrey Eugenides. The wondering eye of post-Beat poet Frank O'Hara, and the stack-blowing combustion of Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso lurk somewhere in the mix too, along with the whimsical and macabre magic realism of a revitalized American graphic novel and fanzine scene. Of course, this being a bunch of dropout twentysomethings weaned equally on Daisy Age HipHop, this is poetry, coarse ground and filtered through Cartoon Network, saturation advertising, rap battles and media savvy.

"I'm really weird with input," reflects Doseone on his influences. "I can't take things in, but when I do I reread them 100 times, so I've memorized a bunch of poets' work - but they're just the ones I stumble on. So I did Galway Kinnell and Marilyn Hacker, and Dylan Thomas of course, Gregory Corso, and I've got a bunch of other people that don't really fill me up: Bill Knott's cool, and Bob Kaufman..." However, his biggest literary influences, he admits, are the friends he has shared his quotidian and creative life with for the past five years. "You may take your cues from the rest of the world and people who are long since dead, but when the person sitting next to you appears to be profound, when he's hitting the nail on the head it's ten times more inspiring. And you have a vested interest in searching for perfect lines."

THE PLEASURE OF THE TEXT

"Somebody was feeding an ostrich strawberries," why? is saying, "so we wrote "strawberry in an ostrich throat". And literally a snake got caught in the wheel well of somebody's van, and we were all scared - somebody had a stick, because rattlesnakes poisonous. Six grown men and two little girls were moving this pen of billy goats. We just thought all this stuff was so interesting, it had to be written down." All this and more at an LA video shoot for a track by Mush Records labelmate Radioinactive, and documented in the song "The Velvet Ant".

I half expect their phone numbers to start with 555. It's the code that's always used in American movies whenever a number is read out, reserved for such fictions so no one gets the freaks on the line. And when you're dealing with the expanding universe of the Anticon collective you find yourself tripping onto a zone of phantasy, or aural delight, of spinning and coruscating dips from the 'real' demanded by street legal HipHop and into somewhere entirely other, where the music and culture has failed to bolster a sense of self.

Much of the music on 'Ten' had its genesis in various rambles, derives which Doseone and why? took at the end of San Francisco's BART line. "We'd go and have an adventure," recalls why?. "One day we got out in the middle of this suburb and walked around all day, and we just wrote down everything we were thinking about. Didn't edit it much at the time, only later.

If rap in the 80s was Public Enemy's "black CNN", for these whiteys it's a poetry journal. A blog as written by Arthur Rimbaud, a space for injokes and outtakes, howls and disaffections, forensic examinations of the observable world and not a little overreaching pretension. You don't need to be black or white to hear how much of the passion, righteous anger and exploratory zeal that stoked HipHop's early years has been sacrificed to the dollar in recent times, and that's one problem the Anticon folks are keen to address.

"I feel related to a lot of parts of this culture," says why? with barely concealed irony, when I ask him whether he currently feels any connection whatsoever to HipHop's patrician fountainheads. "I feel it sometimes, occasionally I feel it in my walk, or in my talk, or," he deadpans, "When I'm havin' sex, I'm just like, 'Yeah, HipHop...'." He breaks down in mirth a few moments later, but his parody of the religious devotion to HipHop's most popular figures, an affluent elite with aspirational appeal, bites hard. It's a form of churchgoing, like so many (youth) cults: founded on ennobled roots, rent by schisms, demanding eternal devotion and mutual respect, public displays of worship, and for some, even a form of martyrdom in prison or in death, all in the name of 'keeping it real'. But for the Anticon collective, nothing could be more of a fabulation-. In the fictions of their own pieces, they are in fact summoning up, carving out a free space intended to be more 'real' than the fantasies and delusions of mainstream culture. "Our stuff comes across as surreal to a lot of people," says why?, "but come on man, when you step back and listen to what the fuck these people are saying, whether it be 50 Cent or Mariah Carey or The Backstreet Boys or Christina Aguilera, that's all fucking surreal, man, that's like some acid freakshow carnival. They're creating comicbook characters and playing them in real life. I don't know how they act when they are at home with their moms or their boyfriends or whoever, but at least in the public eye, they're complete caricatures of - not even themselves - of something that our society at large longs to be. These guys coming out of the ghetto, with this innate hatred of the system, they're really projecting themselves as the godfather don of the system, whereas I think they should be rebelling against it.

"It could be set up by the American government, I don't know," he continues. "The American government gives its money to Def Jam and P Diddy to market this sort of , keep the ghetto culture striving for white excellence, diamond studded mouthpieces and things. Whereas in my opinion there should be an uprising."

By his own admission he's "goin' off" on this issue, but it hits a nerve. The notion of what's real and what's fictional is the recurring one in these conversations. For Doseone, the whole process of making this music, and his rampant collecting, scavenging gene, his propensity to pull soft toys apart to create "reverse head animals", all the rest of it, is precisely a way to preserve a sense of reality while all around are losing theirs. "I think, though, that a lot of what we do is fantasy too, but we like to be accountable for it, as blue collar twentysomethingers. So we do have our reality here, but California has become a bit more of the la-la land and that's a lot of what we feel angst toward the world about. American detached fantasies, cheeseburger flag thing, you know, because what we do, me and Yoni and Dave especially is we really do this every day. Whatever it is, whether it's sewing veins on a turtleneck, or mixtapes... So it really is our reality.

"But it's kind of heavy because I didn't vote and I've never voted, but I'll take a political tone in a poem - all that stuff is beyond the three of us..."

"I would disagree with saying that we create fiction," adds why?. "I think all our attempts are to convey reality as we see it. A lot of our stuff is observational, describing the world around us, but picking out things that seem appropriate, and pointing at these things, saying 'Look at this'. Yeah, some of the stuff comes off as surreal but it's more like when you have those books that's like an extreme close-up, and they say, What is this? A tiny piece of turtle's shell, or something like that. It becomes an abstract thing, but in reality it's just a very up-close look. Put stuff under a microscope, you know..."

cLOUDDEAD pieces originate with reams and reams of text written up by Doseone and why?. It can often be "ten pages of a bunch of shit", as why? puts it, but they'll eventually sit down with the unedited poems and pruning shears to begin honing it into a song.

"We consider the lyrics to be extremely important so we don't flag them all," why? adds. The first four tracks on 'Ten' - words and music - were completed by the two vocalists. Later odd nosdam, after a trial separation from cLOUDDEAD, came back into the fold to work up some new backing tracks and was let loose on the joints they'd already laid down. "I would get the song back with the vocals mixed," he says, "and then I would just flesh the rest of the song around it. In "Dead Dogs Two", I had this music that went on for six minutes. They fleshed out a song in their head, and then figured out melodies apart, and I did a basic track. And when I got to it I was so inspired by what I heard that I broke the verses down to real minimal, what you would consider to be a chorus."

"What we do is," amplifies Doseone, "we're songwriters at this point. But they're not conventional songs by any stretch. Pop music, like The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, Bob Dylan - whether it was pop, or successful, or moved people - it doesn't matter, it had consistency, it had more of the air of a life's work. We try and have that, despite there being maybe a bit of a puerile stamp on HipHop. I think it's very interesting - we get to retain this childish demeanor, maybe because we are HipHop, you know?"

It's odd nosdam who handles a large chunk of the production and beats. nosdam has been making music since only 1998, before which his only musical experience has been as a trumpet player up until fifth grade. At the end of 1997, he relates, "I bought a Dr Sample and an eight track recorder. I didn't know what I was getting myself into. I didn't really understand sequencing or anything like that. I just set out to make stuff. I try to imagine what goes through Prince Paul's head when he was doing the early De La Soul stuff. Same way with Dr Dre - anybody that puts themselves into their music and it shows. Flying Saucer Attack, Hood... When we were making the first cLOUDDEAD record in 1999, I couldn't even think about it as HipHop. We were just making what we felt like making. At the time I was listening to a whole lot of FSA, and Stars Of The Lid, but up until then the first music that I really got seriously into was HipHop. I followed it for about six or seven years, and then gradually got out of it as I got older. I got bored of where HipHop was going."

From space rock nosdam derived the sense of disembodiment and disorientation that has spilled over into cLOUDDEAD's lurching production.

"Kevin Shields put so much time into [My Bloody Valentine's 'Loveless'] - it can't be touched sonically, I don't think. I've always wanted to hear something I've never heard before - I like big, distorted stuff, I like things to sound huge."

Instead of HipHop's attempts to ground you, to make you aware of who you are and where you belong, cLOUDDEAD music - indeed the entire Anticon output - is born out of instability and a desire to foreground a sense of confusion. A profusion of voices interweave and overlap, aural smokescreens are sent up in which vocoders and altered registers of speech cloud the rappers' individuality. Beats are slowed so that, paradoxically, the word rate, with its layers of recitation, word-swaps and cut-in phrases, can dramatically increase. In this sense it's a more accessible version of the dismemberment of the human voice attempted by concrete poets and singers such as Henri Chopin and Joan La Barbara in the 60s and 70s.

IT'S THE WOOD MAN AND HIS SPLINTERING SELF

'Ten's' most spooked track is the single "Dead Dogs Two", in which Doseone and why? observe, with bemused wonderment, a kind of resurrection: two dogs "dead in a field/ glowing on the Oakland Coliseum/ rose up when whistled at/ rib cage inflating/ like men on the beach/ being photographed".

"I think we really let it all hang out," adds why?, "say the stuff we wouldn't even say to our friends. All writing is about having a filter. In that song we were walking around East Oakland, and we were basically describing what we saw, and then we started to elaborate on it and fantasize about it. But I don't think either of us knew why we decided to write about those two dogs that we saw. But we felt related on some level to the dogs. Later Robert Curcio [of Mush Records] would tell me he was convinced this whole song was this metaphor for us coming into the music industry and feeling alienated. I was like, All right, whatever - maybe!"

The song goes on to assume a Ballardian streak, as the observers ponder a catastrophe: "We secretly long to be some part of a car crash/ Long to see our arm stripped to the tendons/ the nudity of swelling exposed vein/ webbing the back of your hand./ To be red tendoned dogs.../ blood breathing by the side of the highway." In Doseone and why?'s lyrics a repetitive interest in decay and death recurs. "Obviously as a human I have an obsession with death," affirms why?, "just like I'm sure everyone else does, because that's the direction we're headed in. So maybe that has to do with it, and to see a dead dog lying on the side of the highway, like on the first record, the "dead dog on the shoulders of 71 [the highway in Ohio]" from the untitled 11th track on the first cLOUDDEAD LP. I saw the dog, and for some reason it spoke to me. But I dunno why, necessarily. I just think we can see ourselves in things that are dead - we see our future."

"Oh man, I had really violent nightmares when I was a kid," says Doseone, trying to account for the recurring tone of his imagery. "Yoni and I, when we write together, we're very close and we sort of arrive at obsessions, we have dual obsessions that we both feel we can go 50-50 on, and they are by no means what our isolated obsessions are. Yoni's vegan, I have red meat in my pocket and butter in my mouth. And then for Yoni, one of the things that he does besides come up with an image and word choices, is he has humor in his pocket. For me, I have the grotesque. The stuff that I read back to Yoni that gives him chills and makes him make this mouth noise that I know he's liking the writing, is always my more grotesque stuff.

"My obsessions are basically from my weak stomach; I'm the sort of person that's always on the edge. In a roomful of ten people I'm probably the most on edge, yet I'll never take a buck knife and take my arm down to the muscle in front of anybody. At my most creative I feel the pull to smash into a million particles or something, and Yoni and I both have a destructive satisfaction. Somewhere between feeling smaller than you ever should have, and feeling arrogance that you learned from a movie or something. It's half imagination and half actually being down to earth enough to know how small you are, how insect, how dead animal.

"I've lived in the city my whole life. Every animal I could ever pet was dead at the side of a road, or a house cat. And nature comes in sharp packages here, and gray paint. We're very much a product of that."

AMERICA'S A BLINDING PLACE FOR NIGHTLIFE

Welcome to the desert of the real, California style. "There's a DVD and magazine out in stores here, boasting of Arnold's all round wonderful-personness, and then there's a huge centerfold with Charles Bronson, and kids with cancer. It's great."

Is it any wonder some of them, the perceptive ones, the ones that keep their neuroses strictly to themselves, are more concerned with visions of complete otherness, a prismatically distorted vision of America's past?

"There's a lot of big bags of empty that you're sold quite early," muses Doseone. "And you're on the moving sidewalk before you know it - you've got the degree and the student loans."

CLOUDDEAD and 'Ten' may well turn out to be the only surviving twin pillars on which this particular group's reputation is upheld. Their first tracks, recorded in 1999, which appeared on a series of three 10's before being compiled on the first cLOUDDEAD LP, were done with all three members. In between times, nosdam left the group at one point, then returned halfway through the making of 'Ten'. "Me and why? were sharing a living room for three months," says nosdam. "And it just got outta hand - both of us were guilty of not being cool to each other, and it just got really difficult to work together." It took a tour of the US with Hood, followed by a lengthy jaunt around Europe - with a brief, inspiring side trip to play an Israeli beach party - to pull the trio together to make the final push to finish 'Ten'. "It's been a rocky road," claims why?, "but I'm really glad we did do this record. That's how I want to leave it: on a good note."

Now, why? and nosdam are both taken up with producing their own respective solo material. With Themselves' Jel, nosdam recently answered a call from Fantomas's Mike Patton to provide beats and pieces for his forthcoming rock/HipHop crossover project Peeping Tom, on which Dan The Automator and others are also feature.

Doseone still retains a little optimism about the future of cLOUDDEAD. "It's so easy with the three of us," he insists. "It puts us somewhere, magically, in the world." He is currently providing the voice for a character in a forthcoming (in 2005) animated movie, Zoo Project, by animator Chris Ruffado. Ruffado makes Animatronic figures (He's making me an Animatronic George Washington bust for my stage show!" reveals Doseone with delight), and apparently built an entire set in his house to film the work. Doseone is voicing a pair of disembodied cartoon eyes that float in the wall cavity of a rundown house.

Even if they've had enough of each other for the time being, you sense an enduring special relationship born of those who've traveled together to their darkest psychic zones. Nowhere in the Anticon catalogue is there anything that so powerfully manages, in Doseone's phrase, "to freeze a moment with sense intact... The three of us found the knack together and then we learned to edit. I think it vaults - we pulled this out of thin air... together."

ROB YOUNG