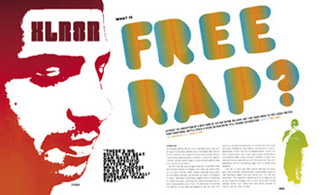

WHAT IS FREE RAP?

WITNESS THE CONCEPTION OF A NEW FORM OF HIP- HOP RHYME DELIVERY, ONE THAT OWES MORE TO FREE VERSE POETICS THAN TRADITIONAL BATTLE LYRICS. A SCENE SO NEW WE'RE STILL ASKING THE QUESTION: WHAT IS FREE RAP?

INTRODUTION

The philosophy behind "free rap" is this. In dictionary terms, rap is verbal slang for conversation between two or more people. Rap is also an art form centered on the creation of musical sounds through informally and formally speaking words in a rhythmic or arrhythmic cadence. "Free rap" maintains that the rapper is a vital instrument able to create music however he/she sees fit.

The term "free rap" pays homage to free jazz, a movement initiated by Ornette Coleman, Eric Dolphy, Cecil Taylor and several other jazz musicians in the early 1960's. Through a seemingly natural evolution from bebop, hard bop, cool, and other jazz idioms, its emphasis on chaotic, spontaneous improvisation, jagged rhythms unsweetened by melodies and hooks, and democratic soloing eliminated most listeners' preconceptions of jazz music. The adventurous musicianship and openness to new ideas promulgated by free jazz have since served as a template for generations of musicians who want to play and create uninhibited by staid traditions and commercial concerns. Appropriately, the term "free rap" has appeared before, usually in articles or record reviews, when writers need to explain or describe an unconventional rapper, group, musician or producer. It seems accurate when trying to understand an artist who sounds as if they aren't bothered by what the record-buying public thinks a hip-hop record should be.

"Free rap" is a term most often used by observers, not participants. Most of the MCs mentioned below would probably simply consider themselves rappers who make hip-hop music, not "free rap". Nevertheless, their eloquence in delineating the art of rapping as well as their respective recordings-many of which sound unlike anything deemed "hip-hop music" before-make them perfect examples for some of "free rap"'s basic concepts.

This article primarily deals with rap in the form of recorded hip-hop music. Those recordings involve numerous vocal takes, the tweaking of a beat to match a rapper's vocal tone or rhythm (and vice versa), and other studio manipulation that often, though not always, eliminates what is normally perceived to be an improvisation, or a single "take" of a song.

In the studio, rappers usually speak words already written by themselves or others. There are exceptions: Chuck D. from the politically minded group Public Enemy and San Francisco MC Encore from the Executive Lounge are two who reportedly sort out rhyme schemes in their head rather than writing them down, before freestyling them at a recording session. But for most, a written lyric, culled from a collection of rhymes or "book of rhyme pages," serves as a template of words a rapper then manipulates into myriad vocal sounds.

CONTENT/CONTEXT

The content of the rhymes can vary widely. Many of them serve as personal positive affirmation, and use a fictitious opponent or "wack MC" to compare and contrast a rapper's numerous attributes. For example, New York rapper Aesop Rock says that when he writes his rhymes, "I basically just think about whom I'm pissed off at." He says he usually writes in four bars, so that each line fits into a quatrain that matches the beat. "I don't like to have that random empty three bars at the end of a verse before a chorus comes on."

RAP TACTICS

In a hip-hop context, rapping is incorporated into three different milieus: freestyle, MCing and written lyrics. Freestyling is rapping without premeditation, when rhyme phrases are generated through the heat of the moment. MCing is moving the crowd, entertaining the audience through wit and banter. Written lyrics are premeditated thoughts patterned into rhyme schemes to be memorized or recited.

In contrast, Canadian MC and Sebutones member Buck 65 says, "It's very basic to be riding on top of the [beat]," or rhyming in perfect 4/4 stanzas, as is hip-hop's convention. He tries to use a more sophisticated approach: "floating around the beat a little bit," inserting words that conflict rather than complement a song's rhythmic pattern without disrupting the song's overall flow. This is known as "rhyming off-beat." The key is to land on the first segment of a measure, or "the one," at the beginning of each stanza. "I'll fall just behind the beat, just like Billie Holiday used to do, or I'll go just ahead of the beat, but once that 'one' comes around again, bam! I'm on it."

Eyedea, one-half of Minneapolis duo Eyedea and Abilities and a member of the Rhymesayers crew, explains, "There's no rules. The beat can have its own specific pattern, but what I choose to do over it might be totally different that that." As a vocal instrument, a rapper can accompany a beat however he wants, while the techniques he employs provide a structure to his experiments.

Rhyme patterns are filtered through a rapper's own idiosyncratic delivery. Awol One, a solo artist as well as a member of a LA group the Shapeshifters, says he sounds like "a robot being eaten by a vampire." Aesop Rock explains his point of view as one of a "harsh realist mixed with B-boy mixed with pessimist." Individuality is a treasured commodity in the free rap game, creating distance between oneself and the rest of the pack. Copycat rappers are derided as wack MCs, punks susceptible to lyrical beatdowns.

Doseone, a member of Oakland, CA's Anticon collective, says he raps like "a veggie burger." Best known as an "abstract" rapper, he delivers his poetic rhymes, which often carry multiple meanings, in an aggressively imagistic vocal style developed during numerous battles against other MCs. Doseone: "There's something about being an MC that's about trying to be the best. It's more crafty than arty."

INFLUENTIAL PATTERNS

Most of the artists quoted here cite Freestyle Fellowship and Organized Konfusion as key influences in their musical development. As Organized Konfusion, Pharoahe Monch and Prince Poetry released three critically acclaimed albums (self-titled, 1991; Stress: The Extinction Agenda, 1994; Equinox, 1997) before splitting in 1998. Birthed in early-90's Los Angeles, Freestyle Fellowship-Mikah Nine, Aceyalone, P.E.A.C.E., Self-Jupiter and, for the first album, J Sumbi-dropped two albums (To Whom It May Concern, 1991; Inner City Griots, 1993), parted for several years, and recently reformed. They have a new album called Temptations.

"I grew up on a lot of different music in my household, the most influential of those musicalities [sic] being jazz," says Pharoahe Monch, who released a solo album, Internal Affairs, in 1999. "I tried to become an instrument lyrically, because I didn't pick up an instrument as a kid and play. I noticed different notations and rhythm[ic] variations in the jazz music that my pops and my brother had me listening to, and I tried to mimic that and bring that into the game lyrically." Pharoahe made his voice replicate the varying notations of, say, John Coltrane playing saxophone, using the rhythm and sound of words to carry it up and down the scales. The breadth of the scales would cause him to speed up his raps until they replicated sheets of sound, to stretch them until they were mere harmonies, not dissimilar to singing. As a result, a Pharoahe Monch rap is an exercise in unpredictability capable of spanning a full range of emotions.

Pharoahe Monch: "The mood or the patterns, the notations, and the sonics also create an emotion and a vibe. That's what I wanted. When you're angry, it's cool to say some angry shit, but it's cool to make people feel some angry shit from you."

"Looking at everything from a jazz perspective, it was easy to see the wide range of styles you could have, from a musician's point of view," says Aceyalone, who remembers how the Fellowship developed as a "breaking-the-rules kind of thing...The rhythm of the world is endless." Calling himself a "technical" performer, Aceyalone uses words rich in similes, "subliminals" (or hidden metaphors) and double-meanings. His raps are typified by a daunting didacticism leavened by vocal flights of whimsy, bending and elongating to place emphasis on important words and phrases.

JAZZ IN A B-BOY STANCE

In a separate conversation, Mikah Nine adds, "Jazz, to me, represents virtuosity in music. Jazz isn't just bebop, or swing, or any of that stuff. It goes on through the post-modernist era to urban music, drum & bass, and r&b." His approach breaks free of rap as a structured art form built around dogmatic wordplay, and incorporates chants, rapid-fire vocals, and harmonizing.

Stylistically, rap can be used as a prototype to further spontaneous, freeform expression in hip-hop music. It serves as a current to be channeled into or against other voices, instruments and sounds, and girds further exploration into vocal communication, whether rapped or not. But searching for your voice within a beat or a rhythm isn't a purely scientific endeavor. Rappers use techniques as torches to guide them through the sounds of blackness. The rest is up to chance. "Even though it is a craft and there's certain techniques involved," argues Aceyalone. "There are certain flavors that you can't explain, the way a person words things based on who he is. A lot of it is conscious and a lot of it is unconscious."

MOSI REEVES