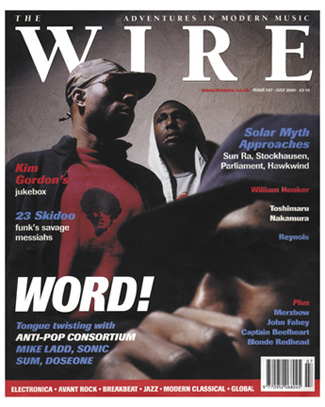

ORAL PLEASURE

If the Word created the world, then wordplay can change it, runs the creed of America's new HipHop underground. Peter Shapiro meets Anti-Pop Consortium, Mike Ladd, Ozone Entertainment, Sonic Sum and Doseone to find out why freestyle storytelling is only now catching up with the complexities of beat science.

Storytelling means more in HipHop than in any other genre except maybe singer-songwriting. So, as the hero of my personal favorite biographical anecdote, Amaechi Uzoigwe (CEO of avant HipHop label Ozone Entertainment and manager of acts like Company Flow, Anti-Pop Consortium and Saul Williams), stands in very good stead. As a young boy, Amaechi moved to Uganda with his family when his professor father was recruited to help Idi Amin's country become Africa's shining beacon. When the family met the dictator, Amin picked up the young Amaechi, who promptly urinated on him.

As most likely the only man to have pissed on Idi Amin and lived to tell the tale, Amaechi naturally attracts the cream of a HipHop community obsessed with mastery and survival. But his coterie of MCs aren't on some Lil' Kim "Money, Power, Respect" trip. Instead, these "orators of advanced thought" are trying to apprehend a very different kind of force: logos. If the Word created the world, then wordplay can change it. From Big Bank Hank's (via Grandmaster Caz) "Hotel, Motel, Holiday Inn" to Outkast's "Packing steel/ Pickin' cotton from the Killing Fields", the notion that language can construct and deconstruct your environment has been a crucial aspect of the HipHop mythos. However, a new group of MCs - Mike Ladd, Anti-Pop Consortium and Sonic Sum (who all record for, or are managed by, Ozone Entertainment), and Doseone, who, as a member of the Anticon collective (which attracted attention last year with Sole's savage broadcast to Company Flow, "Letter To Elpee"), is most definitely not on the same team - are making this implicit undercurrent explicit: remaking HipHop as therapy, as art space, as playground for fantasy (but not of the big ballin', shot callin', livin' large variety).

As members of the first generation to have really grown up with HipHop as a fact of life, not as something that needed to be discovered, these MCs are pushing its sonic and thematic envelope - experimenting with cadences that would make Yoko Ono scratch her head, rapping about abacuses, bird catchers and Glade potpourri - without feeling like they're saving HipHop from itself, without any of that Roots/Common 'We're giving you what you need, not what you want' bullshit. "You look at HipHop right now and it's developed to a point where it can have a fringe element," says anti-Pop Consortium's Priest. "This is like the Dinosaur Jr, Sonic Youth era. We compare it to Bad Brains, we're just trying to bring it faster and harder."

"We totally are the ultimate fans doing this music," Doseone concurs in a separate interview. "What we compromise are none of the golden HipHop rules. We go out there a little bit musically, but we are still hard-nosed lyricists and there's that aggressive thing too. We're still full of male, HipHop energy, but we're trying to be nice with it and we're trying to help ourselves be better people with it... De La Sole, they were out there. We're just picking up their torch and everyone else just ignored it. Two, three years after [1989's] 'Three Feet High And Rising' came out, people and fringe and I still don't know what they were talking about on some of that stuff, but I feel it. And they had that human energy, the way they see their lives, putting it down, making it accessible to everyone. In that respect, I don't think we we're fringe, I think it's always been there. HipHop is always trying to call it stuff: "it's HipHop," "it's not HipHop." HipHop is all samples, everything is borrowed. All we have is that great HipHop energy... People act like we are pouring intelligence into it, but it was always there. De La was hyper-intelligent."

These MCs may make Rakim flow like ee cummings, but they are just as committed to "mak[ing] the beat go around like parallelogram shaped algorithms." Mainstream producers like Mannie Fresh and Swizz Beatz may be all futuristic with their pinging, "Casio superball bouncing around a pinball machine" beats, but these guys and their affiliated producers build a sonic architecture that has more to do with the impossibilities of Congolese artist Bodys Isek Kingelez's 'Models of the Extreme' (paper buildings that look like Las Vegas casinos designed by pachinko machine manufacturers) than it does with any of the producers trying to rebuild Run's House with contemporary materials.

On his recent solo album, 'Welcome To The Afterfuture', and his collaborative project, The Infesticons' 'Gun Hill Road', Mike Ladd's sonic environment is a compressed, claustrophobic, dysfunctional world not dissimilar from that of compatriots Company Flow: synth brutalism, dizzy drum 'n' bass rhythms, ornery horn fanfares, Eddie Hazel guitars, loops that funk like Lurch from the Addams Family, jaunty Bollywood strings suffocated by a jungle of found sound, thick keyboard jalopies, and beats that "talk like Nick Cave, but they don't get you laid." "It's accessing that whole concept that's in a lot of urban music I guess, exemplified by The Bomb Squad," Ladd says, explaining his aesthetic. "How many different styles you are receiving at one time: you have the TV, the radio on, and the stereo coming in from someone else's apartment, and the dog, the cat and the traffic. So, I've always thought of that as an interesting idea. Although I've never executed it to the point where I thought about it, like that dude who recorded the street sounds outside the house and put it through the entire record, you know stuff like that is more deliberate. But that's part of why it gets so condensed. The other part is who I love, the music I love. Like [Rotary Connection's] Charles Stepney... That album [Rotary Connection's 1969 LP 'Songs'] changed my fucking life. I heard that cover of 'Respect' and I was like, 'Wow'. I had no idea you could make music that wonderfully soulful and just out there at the same time, you know somewhere between Shirley Bassey and Iggy Pop... It's ridiculous, he just knows how to do it better than I do [laughs]. I'm getting' there, getting' there. I've got a few more years. It's guys like him: Jimi Hendrix's music was incredibly dense, Funkadelic's music could be really dense. And like all this orchestral shit. I put Carmina Burana in HipHop in 88, goddamit. I want all you to know that; [laughs]. In the studio with Anti-Pop doing the Infesticons record, they kept telling me to take shit out. I thought I made a nice, minimal track. They're like, 'Take more out.' I was like,'Ahhh, this really does work.'I'm listening to a lot of different stuff, thinking about that shit right now. The Cat Power record is really interesting in that way. The new Yo La Tengo record. And obviously shit like Prince, The Black Album. I just went back and listened to that; that shit is ridiculous. Thelonious Monk. I'm still learning stuff, like how do you play with tension... In loop culture, especially if you're a producer, you can get into the habit of just listening to a loop and thinking it's OK. It's not OK. You got to go back and listen to how Brian Eno did it. Why does that shit work? If it does work..."

Of course, the real problem with loop culture is that it will take more than a three-snipit of The Honey Drippers' 'Impeach The President' to overthrow the tyranny of the narrative which has been firmly in place since sometime BC. The art of storytelling may be crucial to HipHop, but aside from De La Soul, it has yet to come up with a form of chronicling that is anywhere near as radical as its beat science. The Infesticons' 'Gun Hill Road' is an effort to change that. It's an epic in the grand style - a Beowulf in Maurice Malone jeans and a Wu Wear skully; the blaxploitation flick Rammellzee never made. Its premise is that an army of robots created by the evil scientist Poof Na Na attempts to jiggify the universe only to meet resistance in the form of The Infesticons - but it's about as linear as a Homeric doodle: "I like rhymin' like Mascis/ My beats are like molasses/ Sweet and slow like Jackie Onassis/ With Alzheimer's/ Social climbers slip on my diarrhoea/ MCs sound the same, like onomatopoeia"; "Like Rin Tin Tin was German/ Like Mengele was killing kin/ Like PM Dawn in sequinned thongs/ like singing songs by Celine Dion." "It came from somewhere way back there reading all those linear notes of Parliament records," Ladd says of the genesis of the project. "I always wanted to do a story like that... I wanted it to be more open-ended. Yeah, it's a concept album, but not really. It's more people flippin' over beats, but I gave everyone a bunch of ideas and said, 'You can follow them if you want to'."

'Gun Hill Road' is not only an attack on Cream Puff and his ilk, but also an assault on contemporary culture's obsession with beauty, shiny things and glamour; it's a plea for dirt and impurity. Ladd has been mixing things up since he discovered HipHop, dancehall and Bad Brains at roughly the same time while growing up in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Although he grew up in the environs of America's most prestigious university, he wants you to know that, contrary to reports in the US music press, he "didn't go to fuckin' Harvard University." "There was an article which said I was born in Brooklyn and went to Harvard," he explains. "It was probably the other way around, which is disappointing to people with HipHop fantasies. That's my forte, bumming people out. I used to freestyle as a kid, like when I was 12 or 13, when HipHop was just starting to hit Boston.

There was a radio station we used to listen to, and they'd play Yellowman and some MCs and if we stayed up late enough, punk rock... My friend used to have this rhyme,"When I was a kid I used to read the comics/ Then I gave my money to Reaganomics/ Now I'm poor and dirty and living in a shack/ Please Mr Reagan won't you give my money back." So it was like that and we were breakdancing. But at the same time there was all this other stuff going on, and I started playing drums and I was in this punk rock band called Uncle Fester. I was trying to add funky beats to that stuff which later became grunge, because John Bonham had already put funky beats to rock a long time ago, a long time before that [laughs]... In college I had this band called the Coalition and I was really influenced by Divine Styler: [his] Word Power and 'Tongue Of The Labyrinth' blew my fucking mind... At the same time I had started getting into poetry; Kevin Powell and Ras Baraka, Amiri Baraka's son, did this book called 'In The Tradition', which was an anthology of black poetry. And I had been really inspired by the Black Arts Movement, which seemed like it was going to have a renaissance in New York, so I moved down just to be a part of that. I was writing with people like [spoken word artist] Tony Medina and that created a good space for me. Third year there, I got a Casio and a big fat Akai and some other basic equipment and I made the first record 'Easy Listening For Armageddon' on that, which was done in 96 and came out in 97."

While the Black Arts Movement partially failed because of its monolithic definition of blackness, Ladd interrogates such as fundamentalism. " I like to think that we're trying to do some post-futuristic soul, trying to extend the tradition of soul music and pushing the parameters of what some people think of as black," he says. "What we're doing is definitely black music even though it's not what people might stereotypically expect, but that's what it is... Soul music and HipHop are different things. All those categories, it's like racism: there are too many genetic differences within each category, so that the categories always end up fucking up and breaking down. There's great soul music within HipHop, and now there's great HipHop within soul music now that the two influence each other... What gets lost in the fetishisation of soul music is that people decided that discipline is not involved in it. But it really is, and that's what is sometimes daunting to me. This shit takes serious work and lots of times I'm using it as a play which I think is crucial, but there's a certain amount of rigour that's involved. Like Anti-Pop, they take their shit very seriously, more seriously than I do. I actually do other stuff, so my shit is focused in different ways, but they just put a concerted effort into my stuff. I first met Beans in 1992 and he was doing the same thing, but every time you see him it's tighter and tighter and tighter. It's so dope to watch people grow like that. That's why I love Anti-Pop so much, it's like watching this incredible evolution. And also their shit is ridiculous."

How ridiculous is Anti-Pop Consortium's shit? Try this on for size - Priest's verse from 'Disorientation', my vote for the dopest rhyme of the year, even though it originally came out in 1997: "High priest, extracurricular illustrator/ Fuck a president, nominate Priest for dictator/ Separate you like binary fission/ Envision division of good and evil/ Believe that you will perish if you don't choose/ Confused over which side of the crater will the creator place you/ In case you don't understand/ Remember Iraq, remember Iran/ Remember dismembered bodies and MCs and SPs melting at ground zero/ Adjust your vision/ Grand exquisite, lyric verbalizer/ Witness the fire/ Break down rhymes through enzymes in my saliva/ Deliver, I'm the liver/ Futuristic inscriber of cities enclosed in plastic bubbles/ You spell trouble P-R-I-E-S-T/ My ESP harder than SP1200 snare taps/ Over bare tracks snapped like bear traps/ Did you hear that? You weren't listening."

'Disorientation' was Anti-Pop's calling card, but the trios of MCs - Priest, Beans and M Sayyid - have been bubbling on the New York underground for the better part of a decade. Beans and Priest were performance poets/MCs on the Big Apple's jazz-not-jazz circuit in the early 90's, often sharing the stage at venues like Giant Step and the Nuyorican Poets Café. They were both members of Sha-Key's Vibe Khameleons and contributed tracks to her 1994 album, 'A Head Nodda's Journey To Adidi Skizm', alongside people like Rahzel and J-Live. While working on the album, they met producer/engineer E Blaize (whom they describe as "the fifth Beatle, straight George Martin") and at the Rap Meets Poetry nights at the Fez they met URB scribe M Sayyid. Last year they collaborated with the UK's DJ Vadim ("through the mail, Unabomber style") on the superb Isolationist album on Jazz Fudge before dropping this years magnum opus, 'Tragic Epilogue'.

As they themselves say, Anti-Pop Consortium "rock like Kilimanjaro": wise, graceful, difficult forces of nature inscribing an imposing, geometrical challenge to all comers on HipHop's horizon. As Priest says,"We're all grown men at this point. It's not like we're 21 or 17, running around all coked up..."

"Fuck that, man," Sayyid jokes. "I'm gonna fuckin' kill you."

"Exactly, exactly," Priest continues. "No punch a hole in the wall' style. All that shit is behind us. We're all family men at this point. It's a different testosterone level... With HipHop being almost 30 years old now, I think that it needs to be shown different things, to be re-educated as to the balance it used to have. In the old days, you had Fab Five Freddy rockin' things on a downtown level as well as Rahiem and all those early Old School cats rockin' it on an uptown level with two belt drives, ghetto alchemy plugged into a fuckin' car battery... You can't be nostalgic about it, though. A lot of it's just romanticized shit. It'd be like if I had a straw hat on right now on some big band shit with a slick back. It's cool as a frame of reference. Avant garde cats of the 50's and 60's were all gospel and blues based as well as the early jazz standards and then they took it to another situation. They had the balance of the two. That's kind of what we represent. All of us are well versed enough in the background, so it's a cross-platform situation."

Indeed, Anti-Pop are anything but Anti-HipHop. They've got the fundamentals down, particularly a collection of some of the most inspirational disses in years: "Knowing your marble-mouthed Marlon Brando mumbles would never humble the tag-team Tony Atlas", "Your world is flat/ Hah hah, you fell off/ Hoping the laws of gravity will bring you back to earth/ If not, OK, your words fall lighter than air/ So float away and disappear into a black hole, son [sun?]," and"On the daily I'm facing more clowns than a John Wayne Gacy painting." But they've also seen enough of the 'unreal' world to take things to 'the next level' (please excuse the vernacular). "All of us went to art school, contemporary art, so we bubble all that together," Sayyid who spent a year in the Survival Research Labs orbit, reveals. "People have all these preconceived notions of what music is and what it should be..."

"All these guys have pretensions like, 'I'm here to educate'," interjects Priest. "Man, the dude's like 19 years old."

"Exactly: get off the soap box, throw the tracks on, here's the lyrics, feel that."

"What you have, right, is that we all grew up in HipHop," says Beans, picking up the thread of the discussion. "You're coming into open poetry form, coming from an art background, so when you take the visualizations of the art stuff into poetry and applying that to what you started in HipHop, that's where our writing comes from."

Despite a shared heritage, each MC has his own distinct personality, his own role within the group's chemistry. Priest is so deep, he only has coelacanths for company; Beans is the weirdo (which is saying something in this company) rapping about "Gene Simmons on crystal methane" and eating MCs like Rolos; Sayyid is the joker, the leavening agent, the one who seems the most typical, but don't let that fool you. His showcase, '9.99', is superficially a nudie bar narrative, standing out in this mini-genre only because of its details. But instead of "meeting you more than half way" like too many thugged out halfwits, Sayyid forces you to do the work, offering a challenge to HipHop narrative as comprehensive as Ladd's in the process: "Who popped the stripper?/ Was it my man blowin' two L's that flipped on some Jack the Ripper/ Or those Siamese cats in the Lex iced like the Big Dipper?/ You paint the picture."

Despite the density of their wordflow, Anti-Pop are, as Sayyid says, ultimately about "negative space." Their music would be unlistenable without it. But it's not necessarily a physical or aural negative space, but a representational or logical silhouette. As Beans says on '3 Digit Wiz', their "motto is: show no teeth." It's an image which crops up a couple of times. If it appeared on a Mobb Deep album, say, you'd think it was a throwaway phrase about being hard and not smiling and letting your defenses down. On 'Tragic Epilogue', though, its coded reference to the pickaninny caricature scratches against E Blaize's "warped geometry", reminding that no matter how futuristic you get, you can't escape history. It's all about disorientation. "Contrary to popular belief, we're not coming straight off the top of the head, free ramblin'," Priest asserts. "There's definitely a lot of thought involved. That tool a long time to write." "Tragic took like three years," Bean affirms. "Mad cuts and Bruises."

If Mike Ladd and Anti-Pop Consortium are MC Eschers twisting trompe les oreilles verbal mazes out of stairways to the nebulae, Sonic Sum and Doseone are the equivalent of Outsider Artists trying to fashion an emotionally direct art out of scribbles, bottle caps, pop culture detritus and rhymes scrawled in crayon. Although there are parallels between the immediacy of Outsiders like Howard Finster and Mr. Imagination and the work of Sonic Sum and Doseone, the closest resemblance is to the French art brut sculptor Yolande Fievre. Their fractured shrink raps detailing psychosis, neurosis and alienation are somehow strangely reminiscent of Fievre's ghostly oneiroscopes (sticks and stones and figurines arranged in Joseph Cornell-style boxes so that they look like a Max Ernst boneyard), taking language beyond representation into pure abstract expressionism.

Of course, like true Outsider Art, Sonic Sum's sleepwalking HipHop isn't the result of a self-conscious process. "Arty?" asks Sonic Sum's MC Rob Smith, incredulously. "Dude, I'm a fucking meathead. I just didn't even know that that kind of scene would embrace us... But there seem to be a lot of people now that are into the more intellectually driven styles of HipHop. Which to me it always was. I hate that whole label thing. If you listen to shit back in the day and cats had, like, mad perfect grammar [laughs]..."

"Back in the day, in terms of song structure, cats would just rhyme forever," continues DJ/producer Fred Ones. "There was no 16 bar rhyme, hook. You know they were just developing. That's kind of what we're doing. We don't really know what we're doing, we just develop it. There's no rules. We don't set up to do a certain thing. We just make sure that it's not a contrived package."

With bassist Erik MO and DJ Jun (and occasional tape loops from the wizard of the Walkman, Myster Bruce), Smith and Fred Ones are developing a music that, on the one hand, is the kind of jazzy HipHop that boho producers like Jay Dee and ?uestlove would die for and, on the other hand, sounds like the Prozac haze of a self-actualization tape. Framing lines like "Take me away, crash me back through plate glass/ Let my wings catch the wind and I'll puncture my armour," Sonic Sum's dream sequence production on their debut album, 'The Sanity Annex', is perfect for lyrics which take HipHop off the street corner and onto the analyst's couch. "We don't just do songs to do 'em," asserts Smith. "We didn't sit down and do 'The Sanity Annex'. There was some shit happening and the summation of it is 'The Sanity Annex'... 'The Sanity Annex' has been a concept of mine for years, about five years in the making. I just kept tabs on my life for five years. It's a collage, kind of. Things were done at different times. There are things there from when I was young and gung-ho, I'm going to take the world with this and I'm going to be the most incredible, flippn' rhyme dude using the illest metaphors and shit like that. It was very surface. Then I went through this really tough time, just living, man. I got fuckin' depressed. It was the only thing that I could truly be good at and truly feel like I was doing anything halfway important. And I went through this thing and I was like, 'Damn, my music's not even keeping me straight now, so I won't go out of my fuckin' house.' I moved into this one-room hole and I just didn't talk to people. And I just got into writing and drawing on my writing influences, like Milton, stuff like that. Stuff that I always thought was weird and shitty, but turned out to come back and be one of the most important things that ever happened to me. But you don't know these things when your dumb and drinking all the time and you're running around like, 'I wanna be a star'. And then when real life hits you and you got all these responsibilities and it's a fuckin' bummer and that's what it's like now... I'm just sad all the time, so that's what you get."

What you don't get on The Sanity Annex is moaning self-indulgence. Instead Smith, riding a tidal wave on the stream of consciousness, chases his demons, grasps at phantasms and flits in and out of reveries. With its fractured imagery and disjointed music, 'The Sanity Annex' never becomes a collection of 'woe is me' diary entries. Which is no little feat given some of its sources. "In terms of the songwriting aspect of it, I'm a fan of the true singer-songwriter type stuff," Smith admits. "I have a lot of respect for people who can really write songs and I'm trying to get more into that without falling into this formula... I've got this thing in my head and I want to make people happy or make them fucking mad or angry or whatever. I have so much respect for people who can nail that because I feel I can never fucking nail it, I can never get that shit right. And everybody's got their one, the one that when they heard it they were like, 'Whoah'... For me, in terms of current stuff, it's Radiohead. The Bends was an important time for me. In terms of HipHop, Rakim blew me the fuck away. I wish I could pull some totally eclectic guy out of the air for you, but it's pretty typical: EPMD, KRS, Kane, Slick Rick. You know, there's so many, it's like everybody's story."

While Smith is an Everyman tripped up by life's ups and downs, Doseone was only ever going to be a freak - HipHop just happened to be his frame of reference. "I grew up in New Jersey, Weehawken, Hoboken, Jersey City," he relates. "I moved around, I was a divorce baby. I went to high school in Philadelphia, college in Cincinnati. Seventh or eighth grade I started hearing De La and Chubb Rock. When I got into high school I met a bunch of kids that I started experimenting with 40s and blunts with; not so much experimenting really. But we were like the HipHop heads of our high school. When [Freestyle] Fellowship came out, we had the only copy [of their records] in Philly, and Madcap and Pharcyde... By the end of high school I started freestyling and I was doing that for three years before I got to Cincinnati... I went to school in Cincinnati, but I went to school for business, though, because I had this feeling I was only going to be able to do art for the rest of my life. If I was going to do that, I didn't want to get a wash-away degree, I wanted to at least get some ridiculous thing that I can... You know, you just get a big receipt, but it was cool because it gave me the confidence to do the record label thing which was nice. So I didn't get much input as far as poetry goes from University, [Fellow Anticon member] Why? And I just started writing our own. I write everyday and I've been doing it for a while; even when I was just into writing raps. I was addicted to it. It started getting more and more personal."

Doseone and Boom Bip's rather amazing 'Circle' is nothing if not personal. It may at first appear to be little more than a self-indulgent curio, but the album soon reads and listens like more than surrealism for surrealism's sake. It's antique and scratchy, yet totally ahead of its time - very similar in effect to the credit sequence of 'Seven'. This feeling of a dialogue between the past and the future is largely down to Boom Bip's music: Dose rhymes to an electro beat, while the ghost of a children's TV show theme plays in the background; wires short-circuit on top of tribal Brazilian beats; head-nodding HipHop beats circumcise a Louis Armstrong trumpet riff; accelerating guitar feedback eventually drowns out an icicle marimba; Boom Bip manipulates Dose's voice so that it goes so fast that it runs into itself, while Serengeti drums double the sound; musique concrete rubs up against chimes twinkling like mobiles above a baby's crib; Morricone harmonicas shadow Wendy Carlos Moogs; Pole/Plastikman submarine dub is filled out by Phanton Of The Opera church organs; circus music echoes Dose's conflation of sex and reminiscences of his mother while he's playing Gin with his girlfriend. The music frames Doseone's regression therapy lyrics perfectly.

Some of Boom Bip's synth-heavy instrumentals are sickly sweet - like calliope whirling around a schizophrenic's mind. With Dose's logorrhoea, different conversations running parallel to each other on several tracks, and Dose moving between his mic persona and (presumably) his 'real' incarnation as a guy named Adam, 'Circle' is HipHop from the lunatic fringe, both touching and touched. 'Poetic License' is a madman's boast: "I can write anything I want... 70 per cent of all Episcopalian blue collar jewellers don't believe in such a thing as collective church and state / I can write Mother Teresa in binary code and 'BOOBLESS' on a calculator." He's obsessed with religion: "I found God, then lost him again in the gathering crowd;" "So Jesus and I go out to dinner/ And everyone keeps nailing themselves to things/ Kinda trying to impress him, you know;" "Jesus wasn't a carpenter/ He was a gardener." "Circle is a lot of reflective poems I wrote about childhood," Dose explains. "The cool things about Circle is that me and Boom Bip were making music, we wanted it to be very eclectic, and the poems are just all over the place. There's the one, 'Slight', on there that's like the Heavy Metal beat and that's one of the happiest poems I've ever written, which are few and far between [laughs]...

There's light poems over heavy material and then heavy poems over really light and fluffy stuff. We're really getting into tracking, like on 'Circle' I used 18 vocal tracks on some of those songs, just having a blast with it, backing up voices."

Dose is part of the Anticon collective (MCs Why?, the pedestrian, Sole, Alias, The Sebutones (Buck 65 and Sixtoo) and beatsmiths Odd Nosdam, Jel, DJ Mayonnaise and Controller 7), a small savant garde based in the Bay Area that is pushing HipHop as far out as it has ever been. On the recent Deep Puddle Dynamics (Dose, Sole, Alias and Slug) album, 'The Taste Of Rain... Why Kneel?', Dose quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes, but as eccentric as his references are, his music is still rooted in HipHop. "We're all major freestylers," Dose says of the collective, "and that's why we're all so loose with what we do and that's why our verses sound so different. Like a lot of rappers, they start freestyling after they do tracks, and we were all diehard freestylers who then got into the meticulous end of it... Freestyling was all I wanted to do for a part of my life. It was this vent. To be honest, when HipHop is dead and gone and only in art books, 50 years from now, I think the one thing that it has been completely generated from scratch, although it is a very sampled art form, is freestyling. I think those guys, like Kerouac, TS Eliot, they would die to freestyle. I think they would love to do spontaneous composition and word expression. It made me more intelligent, going from non sequiturs to telling a personal story; it helps you. I think it should be an afternoon thing in schools. It would help these kids at least find something intriguing about the way their mind works. That was the whole thing and that's why I fell in love with it. Plus, there's all that aggressive battle shit. That was fun too, you got to pee on some trees. I've gotten burned out on battling. I'm a very good battler, but I always lost because people cheat, they take writtens, or you just don't win, judges go their own way. I got burned on that, the whole misogynistic thing. I'd get in and try hard to lose [laughs]. Often it gets too face-punchy competitive where it should be 'Oh, you bested me, that was great.' Mike Ladd and those guys, we're the first ones to grow up on HipHop. We didn't have to invent freestyling, we just got to run with the torch."

Anti-Pop Consortium's 'Tragic Epilogue' is out now on 75 Ark. Infesticons' 'Gun Hill Road' is out on Big Dada. Mike Ladd's 'Welcome To The Afterfuture' and Sonic Sum's 'The Sanity Annex' are out on Ozone Entertainment. Boom Bip & Doseone's 'Circle' is out on Mush. Deep Puddle Dynamics' 'The Taste Of Rain... Why Kneel?' is out on Anticon.

PETER SHAPIRO