WEAPONS OF MASS PRODUCTION

In the ever-evolving world of electronic music, the mass proliferation of easily accessible production software has more than leveled the playing field. The case can be made that it's also lowered the bar, opening the floodgates for all nature of mediocre music to glut the market. Which is why we're posting these two battle-tested soldiers of sound, Boom Bip and Diplo, at the front gate. Both have proven their mettle; Cincinnati-bred Boom Bip carves an iconoclastic path of sonic adventurism that incorporates everything from psychedelia to shoe-gazing, while Florida-raised Diplo evokes a panorama that recalls everything from DJ Shadow to the latest in crunk and Rio baile funk. Innovative, inventive and introspective, they're a powerful and positive representation of all that's right with contemporary electronic music.

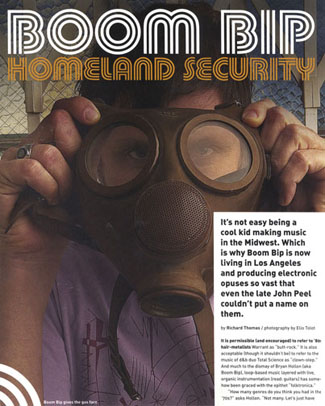

HOMELAND SECURITY

It's not easy being a cool kid making music in the Midwest. Which is why Boom Bip is now living in Los Angeles and producing electronic opuses so vast that even the lat John Peel couldn't put a name on them.

It is permissible (and encouraged) to refer to '80s hair-metalists Warrant as "butt-rock." It is also acceptable (though it shouldn't be) to refer to the music of d&b duo Total Science as "clown-step." And much to the dismay of Bryan Hollon (aka Boom Bip), loop-based music layered with live, organic instrumentation (read: guitars) has somehow been graced with the epithet "folktronica."

"How many genres do you think you had in the '70s?" asks Hollon. "Not many. Let's just have good music and bad music. So much has already been done that stuff is really being recycled and mashed together. As long as you have some sort of thread to connect those styles together, then it works well."

What is his particular thread, I ask.

"I don't know," he replies, smiling.

Hollon and I are en route to a local Army Surplus store to select a few pieces of vintage combat clothing for tomorrow's URB cover shoot, while his iPod spits out an eclectic mix of tunes: Elbow, Animal Collective, The Cure, The Fall, Smith Brothers. For the past year, Hollon and his longtime girlfriend have resided in the Silverlake section of LA in a tidy, colorful apartment atop a modest hill. The area – a mix of dog parks, hip eateries, vintage shops and liquor marts – is a haven of blithe, rustic style. There's enough bourgeois commerce to keep you local, enough crime to keep you honest. It's everything Cincinnati wasn't when he left there two years ago.

"Cincinnati was crumbling," informs Hollon. "It still is. We used to have one of everything, but all the venues started going under."

Race riots in April of 2001 had a profound effect on the city, and the subsequent boycotts by black organizations and performers crippled any remaining cross-cultural appeal. Hollon was stuck in Middle America, armed with two turntables and an Art History degree from the University of Cincinnati. It was time to have a baby or be the odd man out. "There was no room for artists or creative people around there," he says. "I just really felt the urge to get out." But things weren't always like this.

As an undergrad, Hollon's creativity thrived. He Djed constantly, played guitar in a grungy hard-core band and dyed his hair nearly every shade in the color spectrum. Friday and Saturday nights were fueled by 40-ouncers of St. Ides and greasy meals at In the Woods Tavern on Calhoun Street. Everyone was in school, but no one was inundated with work. There was always time for music.

"The beauty of those days is that none of us fit," says Anticon anti-here DoseOne (aka Adam Drucker), Hollon's longtime friend and fellow Cincinnati expatriate. "It was the synchronized blossoming of several creative post-teens on ice. Bryan always had his own center and musical pace – that sensitivity to what's in the world already and what he chose to bring to it. He possessed that all-city DJ mystique. I rarely met someone he didn't know, but pizza delivery might have had something to with that as well."

Basement parties in Dose's McMillan Street apartment brought together a kaleidoscopic group of individuals who would become the core of America's current odd beat aristocracy, including Sole, Why?, Buck65, Slug and Mr. Dibbs. The Anticon record label was in its infancy, and everyone hooked up at least once a year for Scribble Jam, the festival that became ground zero for the indie hip-hop explosion. Robert Curcio, who ran Mush Records out of his apartment, provided an outlet for much of that energy, including the DoseOne/Boom Bip collaboration, Circle.

"The musical ideas that [Bryan] came up with on Circle really stretched the concept of what a hip-hop producer should do with samples," says Curcio. "With Bryan's production, we really started to get the reputation as a label willing to take chances. He was a huge part in helping establish Mush's identity."

The album was a 29-track outpouring of fragmented styles, from hip-hop to country to metal. It was unruly and raw, but it was honest, and it received a wealth of acclaim. Hip-hop heads regarded it as an instant classic, and legendary radio DJ John Peel invited them to record a live session. Anitcon and Mush were firing on all cylinders, and their respective collectives were swelling. Hollon, however, made a concerted effort to operate independently.

"They knew I was a loner and didn't like crews at all," Hollon explains. "Not because I didn't like what they were doing – I loved it – but I don't work well with collectives. It's hard to find your true sound when you surround yourself with people who are constantly criticizing what you do."

But no one is more self-critical than Hollon himself. A self-professed perfectionist and control freak, he'll work through a track until it gives him nightmares. (These usually involve iguanas and/or alligators in various stages of attack). By the same token, he refuses to bang his head against a track that isn't going anywhere, and he doesn't horde material.

"I could have 500 beats lying around," he confesses, "but I delete the shit. I've probably gotten rid of a lot of good ideas doing it. I think it's just my obsessive-compulsive nature."

Hollon is by no means self-effacing – just incredibly self-aware – and his motivation is clear and commendable to his friends.

"I've always admired Bryan's ability to be solo as a music-making entity," relates Dose, "as I'm sure he admires my bohemian living, record collective life pretzel. Whatever separated us in terms of distance and labels never really existed between the growth of our aesthetics."

Despite his creative autonomy, Hollon was never really alone. He had friends and a job and an incredible girlfriend, but one by one, people began to leave. By the time he started work on his first solo album, Seed to Sun (Lex), he was very much by himself. Does had moved to San Francisco, Fat Jon had moved to Berlin and Mr. Dibbs was constantly on tour. The Cincinnati riots and September 11th hit the city like a one-two punch, and Seed to Sun, with its noise collages and ominous funk, was Hollon's emotional barometer. Breathy, stream-of-consciousness collaborations with Dose ("Mannequin Hand Trapdoor I Reminder") and Buck65 ("The Unthinkable") invoked images of ghosts and bleeding eardrums; mail order litanies on a "dying city."

"I know that sounds horrible," admits Hollon, "but that's all I saw. I was not going to spend another 10 years of my life in this."

Ironically, one song on Seed to Sun – his least favorite, and one that almost didn't make it on the album – single-handedly recalibrated his direction. "Roads Must Roll," the album's sun-patched opener, was licensed by Lloyds TSB Bank for a six-month UK ad campaign. The track was also featured on a few prominent downtempo compilations, and recently showcased in the Jay-Z documentary, Fade to Black. With Circle on his resume and a new lable (Warp subsidiary Lex) in his corner, Hollon spent seven months touring and knocking back drinks with the likes of Marcus Eoin and Michael Sandison of Boards of Canada. His first international gig put him on the bill with Aphex Twin.

"To see all the clubs I'd heard about and meet some of the people who had supported me felt so good," he remembers. "It wasn't like I had some intense agoraphobia and felt, 'I gotta go home.' I was like, "Bring it on. This is what I want to do for the rest of my life: Travel and do music.'"

There was no way he could remain in Cincinnati, and 10 months after Seed to Sun hit the shelves, Hollon and his girlfriend packed up and hit the road. He used his earnings to furnish a home studio and immediately began to orchestrate a Seed to Sun remix project. The album, entitled Corymb, featured reinterpretations by Lali Puna, Four Tet, Boards of Canada, Mogwai and more, as well as two Peel Session cuts. (Though a few artists inquired, he did not open up "Roads Must Roll" for a remix.) His mindset acclimated to the temperate Los Angeles conditions. He sopped up new inspiration everywhere he could find it, from rock shows to coffee shops, and his music billowed with romantic intensity. Did it soften his obsessive-compulsive nature? Not really. He still consumes only modicums of caffeine for fear of bugging out and walks into doors that aren't open. His brain still moves a million miles a minute, perpetually processing all of life's possibilities, both musical and otherwise. But he's found a new home and a new center in his tidy, colorful apartment atop a modest hill.

"He's got cooler clothes and has fruit trees in his yard," laughs Dose. "These things have a significant effect on recording and living habits. He's twice the motivated human being since he's been in LA."

Blue Eyed In the Red Room (Lex), his new full-length, pulls every influence into focus, but remains an uncomplicated affair. Reflective, meandering tunes like "Dumb Day" and "One Eye Round the Warm Corner" are galvanized with hope and emotional possibility, and "Eyelashings," Hollon's favorite track, is sweet bipolar melody. His hip-hop roots are there, but they reveal themselves in each song's minimal structure. Unlike the compositions on Seed to Sun, these are stories that read themselves to the listener, not the subplots awaiting to be excavated.

"That extreme, bizarre experimentation with sound influences me," Hollon relates, "but I'm a big fan of simple melody and simple songs. If I look back, my favorite songs of the past 100 years have all been pretty simple."

Blue Eyed continues this theme from a vocal standpoint. Complex raps are replaced by ballads offered up by Gruff Rhys of the Super Furry Animals and New York singer/songwriter Nina Nastasia. The latter's contribution, "The Matter (Of Our Discussion)," is a beatless bullet straight to the heart that's designed to be the closer on many a mix. Hollon knows this liberal assortment of styles will not draw criticism as much as it will spark more discussions about what kind of music he makes. Some will say he's abandoned hip-hop, and you can be sure the folktronica label will rear its ugly head. The fact is, Circle will remain a benchmark release for abstract head-nodders, and his ties to Warp will always foster new relationships with the bit crushers. Everything is copasetic.

"John Peel was talking to me a while ago, and he said 'Someone asked me the other day what I should call your music, and I had no idea.' Coming from John Peel, that's a huge compliment. If John doesn't have any idea, no one else on the planet should have an idea of what to call this. And that's where I'd like to keep it. I like to be on the fence."

RICHARD THOMAS